Ron Schott of Ft. Hays State University gave an excellent presentation that made this particularly clear. The gigapan system is elegant in its simplicity and it offers an avenue for simply depicting the elegant complexity (good one, no?) of huge geological vistas and outcrops. It even has an application for looking at very small things in a big way. Check out Ron's blog for some details.

What is Gigapan? Well, it is a system for taking a panoramic photograph that is composed of many, many, small and detailed photographs. Presumably you have personally attempted to make your own pan photos, say, with a software package or with a built in camera function. Dare I say that you probably didn't wan't to try to stitch together more that 5, maybe 6 photos, right? You probably stopped at 3 or 4...like the image below:

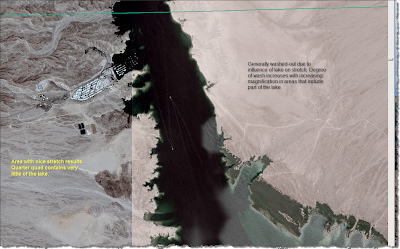

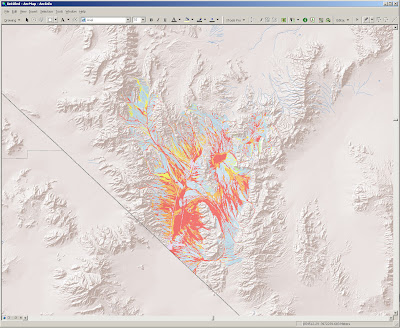

The Gigapan cranks this technique up a giganotch by stitching together 10s and 10s of high-resolution images into a...wait for it...Gigapan. The image below is a faked example to illustrate the difference between your approach and the Gigapan approach:

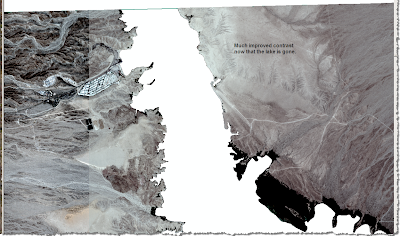

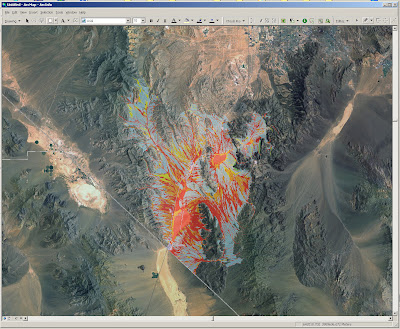

So. Why would you want to do this? Well, for one thing, it is totally cool. For another, it offers an exceptionally efficient way for exploring a large outcrop or geoscape. Once you have taken this series of images, stitched them together, and uploaded the result to the Gigapan site, you can view it at all levels of resolution. In the case above, you can bask in the glory of the huge stack of intracanyon basalt flows on the Owyhee River. Then you can zoom in and look at the complicated cooling structures in great detail. Then you can zoom in and check out the contacts between the flows. While you are at it, you can check out the thin beds of gravels sandwiched between the basalts, etc. etc.

While you are looking at the details, you can pull out images that illustrate some of the aforementioned features. These high-res thumbnails can then be tagged and described for your colleagues to check out. They can then do the same thing and point out obvious stuff that you missed.

I already have my Gigapan gear en route. It works with my existing digital camera collection and is shockingly cheap. Stay tuned for some obvious examples of the application of this to geological studies. Also, stay tuned for the NeGIGAvada project...it is coming. Or should it be GIGAvada?